Expeditions

The First Crossing of Greenland (1888-1889)

In 1888 Fridtjof Nansen, together with five companions, became the first to cross Greenland’s inland. They spent six weeks skiing across the ice cap from east to west and had to spend the winter 1888-89 at Godthaab (Nuuk) on the west coast before they could get a ship back to Norway.

In 1882, during four months Nansen spent on the sealer Viking off East Greenland collecting marine specimens, he glimpsed the mountains which enclosed the unknown interior of Greenland. This awoke an interest for the relatively unknown region. The following year he heard that Finnish-Swedish Arctic scientist Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld had returned from Greenland after an expedition towards the interior and his report of the vast area of ice and snow inspired Nansen to plan his own expedition to cross all the way over.

Apart from the experience itself, the expedition would finally prove what the interior was like and – as a scientific extra – could give information relating to conditions in north Europe during the last glacial period. In 1884, while working on his doctoral thesis, Nansen worked out his plan, which was extremely radical. Instead of starting at a populated point on the west coast, as all previous expeditions had done, he would go from the almost uninhabited east coast. In that way he needed only to go one way in order to reach settlements and a ship back to Norway, at the same time “burning his bridges” since a return to the east coast would be useless. "I have always thought that the much-praised line of retreat is a snare for people who wish to reach their goal,” he stated years later. The only possible way was Forward (Fram in Norwegian) and this was, in his opinion, the best incentive – “west coast or die”.

The area around the Sermilik Fjord west of Angmagssalik at 65⁰35' N was chosen as the starting point – Angmagssalik being at this time the northernmost Inuit settlement in east Greenland. Christianshåb by Disco Bay was the goal, a linear distance of 600 km away. The bold plan was met with considerable scepticism in knowing circles.

Nansen was prepared to pay for the expedition himself, but applied to Kristiania (Oslo) University for 5000 kroner (kr 362 000 today) in order to emphasise the scientific aspect of the expedition. When this was turned down for budget reasons, the Danish merchant Augustin Gamél kindly offered to finance the ski trip.

As Roald Amundsen was to do some years later, Nansen paid great attention to detail with regard to the equipment and provisions the expedition needed. Clothing, footwear, skis, cooking apparatus, tent and food were all carefully studied and modified in relation to the standard type.

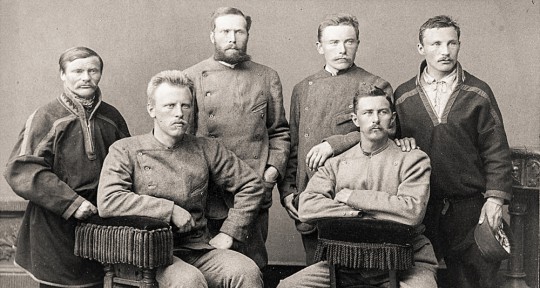

Nansen (26 years old) chose as his companions skipper, farmer and skier Otto Sverdrup (33), army lieutenant Oluf C. Dietrichson (32), sailor, forestry worker and skier Kristian Kristiansen Trana (24) and the Sami Samuel Johannesen Balto (27) and reindeer owner Ole Nielsen Ravna (46). Sverdrup became second-in-command.

On the ice along Greenland’s east coast

The sealing ship Jason fetched the men from Iceland 4 June 1888 and they met the drift ice the following day. It was already well-known that the ice flowing southwards along Greenland’s east coast was difficult for ships to penetrate, particularly before the end of the summer. 11 June was a clear and fine day and they were c. 70 km off the coast near to Angmagssalik. It looked promising, but Jason’s attempts to push through the drift ice were in vain. A whole month passed by and the sealing season was drawing to a close.

On 17 July they were only 20 km from Sermilik Fjord and Nansen decided to make a dash for the shore through the belt of ice in two rowing boats, the one brought by him and the other donated by Jason’s skipper. The boats were packed and the last letters written. Sverdrup was put in command of the one boat with Kristiansen and Ravna, while Nansen was in the other with Dietrichson and Balto. They could at last start their expedition.

However, the shore was not won so easily. The rowing trip started off well, but then strong currents and ice threatened to crush the boats and they had to pull them up on to ice floes. They had been struggling for 15 hours on what had originally seemed like a short and easy trip to shore, and they now raised the tents on the ice for a well-earned rest.

On 19 July the weather cleared again and they could still see land by the Sermilik Fjord, but now at twice the distance. A new attempt was made to row in, but again they had to pull up on to the ice. They were caught in a current that took them rapidly southwards and away from the fjord. On 20 July the waves increased in size and started to break over the ice floe. Originally c. 30 m in diameter, it now broke up into smaller floes which were driven nearer and nearer to the coast and the breaking waves. The men managed to move over to a larger and thicker foe, but the situation was critical.

At one point Ravna and Balto suddenly disappeared. Nansen searched for them and finally looked under the tarpaulin on one of the boats. He found the two at the bottom of the boat where they had given up and prepared themselves for the inevitable death. A while later the weather changed to sunshine. They were now c. 55 km south of the mouth of Sermilik Fjord with an increasing distance from land. Even this last, solid floe started breaking up and the options were not good.

Finally they had to launch the boats and hope for the best. They could only hold out, try to sleep and be as rested and prepared as possible. As they crept into the sleeping bags, the crashing of the breaking waves was deafening and the water foamed outside the tent walls. The ice floe rocked like a ship in heavy seas and Nansen expected that Sverdrup, who was the watch, would call them out at any moment, but nothing happened. When Nansen woke up in the morning, he could only hear distant rolls of thunder. The ice floe was badly damaged and covered in lumps of ice that had been thrown up.

The tent stood at the edge of the floe and close by a large iceberg rocked up and down and threatened to fall over the tent. The sea washed over the floe on all sides, but the mounds of ice lumps protected the tent. The boat that Ravna and Balto had hidden in was washed over by a huge wave and Sverdrup had to hang on to it as well he could. When all seemed lost and the floe was moving into the breaking waves, it changed direction and with unexpected speed rushed towards the land. They had survived the expedition’s most dramatic episode. Continual watch was held in two-hour shifts in order to alert the others of any changes in the ice and sea conditions. They were all worried. They risked drifting out into the Atlantic and disappearing there, although Nansen was sure they would get contact with land in the end.

After a couple of days more the ice thinned out. Breakfast was eaten quickly and the boats were launched. They were now in open water, and with Norwegian and Danish flags flying they rowed towards a steep cliff. Shortly afterwards they were safely in a small bay, were able to step ashore, prepare a good dinner and drink cocoa. Now the job was to get further north again, as they had been carried 380 km south of where they had left Jason. The northward rowing along the coast was hard and they were often in danger from rocks falling from the cliffs. After some time they met a small group of Inuit. Gifts were exchanged and needles were exchanged for meat as the concentrated food Nansen had brought did not stave off feelings of hunger.

Before leaving Kristiania Nansen had promised that there would be enough to eat and drink. Every day the men could eat their fill. Now they were in the awkward situation of having to ration the food. Balto complained and meant that none of them had been able to eat enough after they arrived at the coast. In addition they were ordered out to all kinds of strenuous work. Nansen on the other hand meant that he had never promised anything regarding the food. He maintained that the provisions would only last to the middle of Greenland if they all ate without restrictions. When Kristiansen arrived back home he was asked if they had had enough food. His reply was that “No, he had never been full up”.

Finally on land

At last, on 10 August, they were at Umivik. Here they camped and Nansen decided it should be the starting point for the crossing. The preparations for the ski trip itself could now begin.

They had left Jason on 17 July not far from Sermilik Fjord, which was the planned starting point for the trip. On arrival at Umivik, 25 days later, they had travelled c. 800 km in the boats and were c.110 km south of Sermilik Fjord. At last they could continue, but the starting point was different and they had lost a lot of time. Nansen and Sverdrup made a reconnaissance trip inland up to c.125 m. From here they could see over to a glacier further in. It was heavily crevassed, particularly across.

To climb up from the northwest was therefore out of the question. They chose another route, but even then had to move slowly between crevasses. As they advanced further inland the crevasses lessened and it was easier going. On the other hand the snow became heavier and they regretted not taking skis with them. At last they reached the top of “The White Mound” as they called it, c. 900 m over sea level. From here they saw in over Greenland and concluded that the inland ice looked easier to travel over than they had expected.

Equipment

The sledges were of strong ash, lashed together without nails to keep the elasticity. The length was 2.9 m, width 0.5 m and the runners of elm and maple were 9.5 cm wide, shod with screwed-on thin steel plates which could be removed. The weight was 11.5 kg without the steel plates. With the plates they weighed 13.75 kg. Nansen had wanted to use strong sledge dogs, but had not been able to get any before departure.

All the men had skis and with some in reserve. They had also brought Indian snowshoes which they thought would be useful for pulling the sledges uphill. Some Norwegian snowshoes they had brought turned out to be too small.

The tent was square and made of five pieces, two sides and two ends of light, waterproof cotton canvas, with a floor of coarser sailcloth. This was later used as a sail. The five parts had to be tied together with cords. Unfortunately the snow penetrated through the lacing and it would have been a great improvement if the parts had been sewn together.

The cooking apparatus had been constructed by Nansen as a modification of American Adolphus W. Greely’s patent. It consisted of a burner with two cooking pans where the heat was passed around both pans for maximum efficiency. From snow with a temperature of about minus 40 degrees they could get five litres of hot chocolate in the one pan and four litres of water in the other by using 0.35 litres of methylated spirits. Drinking water while the men skied was provided by melting snow in a flat tin hip flask.

The food was as nutritional as possible in relation to its weight. They had Swedish crispbread, meat biscuits and pemmican which turned out to be made of dried meat without fat. They therefore came to suffer from a craving for fat. They had butter, but far too little. In addition they had chocolate, cheese, dried halibut, pea lentil and bean soup, calf-liver paté (which froze and had to be chopped with an axe), dried caraway shoots, cranberry jam, condensed milk, tea and strong coffee extract, amongst other provisions.

They did not take alcohol to drink. Nansen said about this: “Alcohol in any form is, in my experience, absolutely reprehensible; it gives perhaps a little warmth and enjoyment straight away, but one has to pay for it later”.

He was more positive to tobacco when it is “enjoyed in moderation, but also that relaxes the body strength and weakens the nerves, endurance and toughness all round”. Therefore he only took enough tobacco for one pipe each on Sundays and special days such as anniversaries.

A large number of instruments of different kinds were taken, including purely scientific instruments for collecting air samples and other data. In addition there were of course expedition instruments such as compass, theodolite, pocket sextant, thermometer, pocket watch, photo apparatus (Nansen being an early user of the new Eastman roll film camera), telescope and barometers. Two double-barrelled guns were taken, of which one with pellets, plus crampons, rope, ice axes with long bamboo poles to double as ski sticks, scales to weigh the rations, burning-glass, flint and steel and matches, methylated spirits, a small medicine kit, tarpaulins, and a sack each with reserve clothes – amongst much else.

To the mountains

On 15 August they were ready. The original plan of setting off from Angmagssalik had been abandoned and Umivik was the new starting point, with Christianshåb still the goal. The sledges were loaded with more than 120 kg, which turned out to be too much. Therefore they rearranged the loads to be c. 100 kg on four sledges and the fifth, being much heavier, was to be pulled by Nansen and Sverdrup.

On the first day they made 4 km and up to a height of 180 m. Already on 17 August the weather kept them in the tent for three days.

The many and large crevasses in the ice were a problem, but on 21 August they were up on the inland ice cap and had left the crevasses behind them. Now they had no access to water and the only drinking water they had was the snow they melted in the tin flasks they carried inside their clothes. In four days they had skied 18 km from start and up to 870 m in height. The gradient was more even now, but still there were steep areas where they had to be several pulling each sledge. The snow conditions were good and their progress likewise, but this did not last. New snow and frost spoilt the glide of the steel-covered sledge runners.

They tried using the oilskin sleeping-bag covers as fuel, but this was only partially successful as the tent became filled with smoke and soot. There was more success when the fireplace was moved outside. On one occasion Nansen knocked over the bean soup which was cooking in the tent and it flooded over the floor together with snow, ice and burning alcohol from the stove. The soup was scraped up from the middle of the floor and poured back into the pot.

By 27 August they had reached a height of 1880 m. How much higher they would have to get was anybody’s guess; this was undiscovered land. On the same day they rigged the sledges and set sail, which the two Sami were very much against. The sledges were put side by side, and with the ski sticks across them were lashed together like two rafts. The tent floor and two tarpaulins were used for the sails. The goal was still Christianshåb.

A headwind and bad snow conditions made it steadily less certain that they would reach Christianshåb. It was 595 km away and it would be far out in September before they arrived. The last ship would by then have been long gone for Copenhagen. To Godthåb it was only 470 km. The disadvantage was that c.100 km at the end of the journey would have to be across bare ground with deep fjords and high mountains.

The sails were set and they had decided to try for Godthaab instead. On the way they had a number of accidents. Kristiansen twisted his knee and had trouble walking after catching his ski on a hard sastrugi. Ravna and Balto suffered from snowblindness. Loose snow made the use of snowshoes necessary. After they had mastered the technique the snowshoes were of great help, but after a few days they put on skis again. That was after all the best method, they all thought.

The three weeks that now followed were characterised by monotonous toil. The snow conditions were heavy and the fine drift snow which fell was like sand to walk on. Thirst, cold and a craving for fat were daily torments.

When Nansen crawled into his sleeping bag on 11 September he put an alcohol thermometer under the pillow; it sunk far below the scale of minus 37 degrees. In the mornings the tent was always covered on the inside with frost. Meteorology professor Henrik Mohn later calculated that the expedition had had temperatures below minus 40 degrees during the nights. The day temperatures varied between minus 20 and minus 15 C. Nansen usually arose an hour before the others in order to prepare breakfast, not trusting them with the patent alcohol stove.

The struggle to pull the sledges through the white desert continued. After two hours a bar of meat chocolate was usually distributed to each. The dinner was eaten sitting on the sledges. With a small letter weight accurate portions were measured for each man. After another couple of hours, around 5 pm, they had “supper”. They then pulled until evening, only interrupted by a short rest and another bar of meat chocolate. The evening in the tent was the climax of the day. The evening meal was usually hot soup or stew.

The craving for fat was strong and the butter tasted particularly good. A quarter kilo of butter was portioned out to each man once a week. The best experience was to eat the butter in big chunks. Almost as good was the tobacco. The pipe they had each Sunday was stretched out; first they smoked the tobacco, then the ash and the wood in the pipe bowl. Not having tobacco for the whole week, some of the men stuffed tarred rope into the pipe to smoke. Others just chewed the rope. Nansen tried this, but found it tasted too foul. On the other hand he discovered that it was fine to chew on bits of wood. That kept the mouth moist and helped against the thirst. Since fuel for heating and melting snow and ice was limited, water was scarce. Thirst and fat craving were constant companions. The total daily food ration of c.1 kg pr person was not sufficient either.

To be sure of keeping to the correct course the daily positions were faithfully noted, and meteorological observations were made every few hours.

The top and the descent to the west coast

On 4 September they had passed the highest ridge which was 2 720 m over sea level. By the 11th they were down at 2 600 m and they reckoned that they would soon see bare land. They had calculated that 125 km remained. In actual fact there turned out to be 190 km left to the goal and therefore there could be no land in sight yet.

On 17 September two months had passed since they had left Jason. The next day the wind increased and at last there was a promise of good sailing wind. Despite Balto’s assurance that sailing on the snow was absolute idiocy, the sails were set. The sledges were lashed together in pairs, with Sverdrup, Nansen and Kristiansen manning the one and Dietrichson, Ravna and Balto the other.

As they sailed on that same afternoon Balto suddenly cried out “Land ahead”, and through the driving snow they glimpsed a mountain top. The course was changed towards the top and they rushed along. Nansen was steering. As darkness began to fall he saw something dark ahead. Interpreting it as shadow he continued on. Suddenly he understood it was something else, and he managed to turn the sledge into the wind – at the very last moment as he stood at the edge of a wide crevasse. He managed to stop Dietrichson’s sledge and the situation was under control, but it had been right before the expedition could have ended there and then. They were now back in a crevassed area, but as the weather cleared and with the moonlight they could see well enough to avoid the worst crevasses.

While Dietrichson and Balto erected the tent on the evening of 21 September, Nansen, Sverdrup and Kristiansen inspected the ice around. They were tied together with rope since the ice was unusually difficult with sharp edges and cracks. Nansen saw a dark patch between the ice ridges that looked like water, and when he stuck his ski stick in it was wet. They threw themselves down and sucked up all the water they could manage. After having been thirsty for so long with inadequate rations, it was an indescribable enjoyment to be able to drink all they wanted. The following days they walked across the glacier until they could look down on to one of the arms of the Godthaab Fjord.

On the morning of the 24th Nansen came to a steep slope. Under him there was bare land and the ice poured down to an ice-covered tarn. Soon all the men stood at the edge, and then they set off down the slope. They continued over the tarn and then removed the crampons they had used for the past few days on the glacier. The inland ice cap had been crossed in 41 days. It was a good feeling to have ice and stone underfoot. The nearest fjord, Ameralikfjord, cut into the land south of Godthaab, and now they had to get to the inner end of the fjord. They took as much of the necessities with them as possible and left the rest in a heap on the sledges, covered with tarpaulins ready to be collected later.

The goal

On 26 September they at last stood on the shore of Ameralik Fjord. In many places along the banks there were two metre high thickets of willows and alder. The question now was how they could continue. It was decided that they should build a boat, and Sverdrup and Nansen should use it to reach civilisation.

For the frame they used two long bamboo poles and a bamboo ski stick. For ribs they wanted to use the bent ash lathes from the sledges, but it would take several days to fetch them. They decided therefore to use willow branches. With hard work and a good portion inventiveness they managed to complete the frame. The sailcloth that had been the tent floor was sewn into boat shape and stretched over, and one of the most original boats was created. It was 2.56 m long, 1.42 m wide and 61 cm deep. The stern was given a blunt form.

The boat was only large enough for two and was not particularly fine to look at. Nor was it easy to row, but they made four oars, using the fork-shaped willow branches as oar blades, lashed to the ends of four bamboo poles. The most difficult challenge was to make the thwarts. The round and thin theodolite stand became the one, while the other was made of two thin bamboo poles.

They took with them the necessary clothing, a rifle, ammunition and provisions and were surprised at how much the boat could hold. In addition it turned out to be quite easy to row.

They started on 29 September. After some hours on the thwarts their whole bodies ached. In the evening they went ashore. Nansen had shot six large gulls and they now ate two each. When Sverdrup was later asked whether they had cleaned the gulls well beforehand he replied: “Oh I don’t know. I saw that Nansen scraped something out of them, I suppose some of the intestines, and the rest I presume went into the soup. But I have never eaten better food”. The heads and feet went down as well.

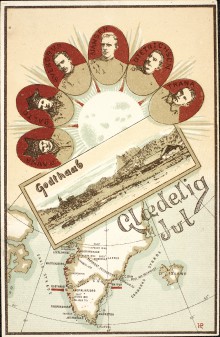

To Godthaab

For the next two days they had a headwind, but the boat worked well. Well into the day on 3 October the wind blew up the sound towards Godthaab. After a while they spotted several Eskimo houses and people streamed out, pointing, gesticulating and talking. They were naturally amazed to see two men in a half-boat. The boat and all the equipment was taken ashore and a blond man came to greet them, speaking English since he supposed that Nansen and Sverdrup were ship-wrecked American sailors. The nice man was Gustaf Baumann, the acting governor of Godthaab. He could tell Nansen that the last ship of the season to Copenhagen had left before the Norwegians had even started their ski trek. There was no other ship in Greenland which could be reached now. The only ship, the Fox, lay 500 km away in Ivigut and would leave in mid October. They could just forget arriving home in 1888. They had arrived at Nyherrenhut, a Moravian mission station a little south of Godthaab.

Moving on to Godthaab they were greeted with canon salutes, the Danish flag flying high and with invitations to dinner. For the first time in months they could put their heads into a washbasin and have an all-over cleanup. They changed into clean underclothes and felt like new.

There were two important matters to attend to. Firstly they had to fetch the other expedition members and then try to get a message to Fox in Ivigtut. After Nansen had sent provisions of food, tobacco, pipes and more in kayaks to the men, he received a letter in return from Dietrichson who could report that all was well and that they were very satisfied with all the gifts. A boat was then arranged to fetch the four, and on 12 October all the expedition members were united in Godthaab. Towards the end of October the Inuit who had been sent to the Fox returned in their kayaks to report that the captain could not wait for the Norwegians, but was taking their letters and telegrams back to Scandinavia.

Nansen wrote of the stay in Godthaab: “And so we lived for the winter in Greenland and had an interesting and in many ways instructive time together with the Danes in Godthaab and together with the Eskimos there and in the district. We studied the Eskimo way of life and tried to learn how to paddle a kayak and go hunting. They are a remarkably unspoiled and appealing people of nature, with simple social relations and way of life, where envy and avarice and class differences have not made the people greedy and jealous.”

During the winter Nansen spent much time with the Inuit and wrote the book “Eskimo Life”. Here he described Greenland and the Inuit, kayaks and kayak equipment, the winter houses, tents, umiak boats and travels, personalities and social conditions, relationships and marriage, morals, justice, drum dancing and entertainment, funerals, art and literature, religious beliefs and superstitions, and also the Europeans. He took home with him a collection of artefacts from Greenland which is now in the Fram Museum.

On 25 April 1889 the Hvidbjørnen arrived as the first ship of the season and brought them to Copenhagen 21 May. Here Nansen could meet and thank his benefactor Gamél.

Home

After a week of being celebrated there, the group left on the Danish mailship for Kristiania, where they arrived 30 May. Hundreds of admirers waited to greet them, together with a fleet of steamships. As they approached the harbour and the castle and saw the quay covered with people, Dietrichson asked: “Look, isn’t it wonderful with all the people, Ravna ?”. “Yes, wonderful, very wonderful, if it had only been reindeer”, he replied.

Read the whole book in English (1909-edition) at:

THE ROUTE OF THE GREENLAND EXPEDITION:

| 17 JULY 1888 | GREENLAND'S EAST COAST |

| 10 AUGUST | UMIVIK |

| 26 SEPTEMBER | AMERALIK FJORD ON THE WEST COAST |

| GODTHAAB | |

| 30 MAY 1889 | CHRISTIANIA |

- Expeditions

- Vessels

- Explorers

- Nansen, Fridtjof (1861-1930)

- Sverdrup, Otto Neumann Knoph (1854-1930)

- Amundsen, Roald (1872-1928)

- Amundsen, Anton (1853-1909)

- Balto, Samuel Johannesen (1861-1921)

- Baumann, Hans Adolf Viktor (1870-1932)

- Bay, Edvard (1867-1932)

- Beck, Andreas (1864-1914)

- Bentsen, Bernt (1860-1899)

- Bjaaland, Olav Olavsen (1873-1961)

- Blessing, Henrik Greve (1866-1918)

- Braskerud, Ove (1872-1899)

- Dahl, Odd (1898-1994)

- Dietrichson, Leif Ragnar (1890-1928)

- Dietrichson, Oluf (1856-1942)

- Doxrud, Christian (1881-1935)

- Ellsworth, Lincoln (1880-1951)

- Feucht, Karl (1893 – 1954)

- Fosheim, Ivar (1863-1944)

- Gjertsen, Hjalmar Fredrik (1885-1958)

- Gottwaldt, Birger Lund (1880-1968)

- Hansen, Godfred (1876-1937)

- Hansen, Ludvig Anton (1871-1955)

- Hanssen, Helmer Julius (1870-1956)

- Hassel, Sverre Helge (1876-1928)

- Hendriksen, Peder Leonard (1859-1932)

- Horgen, Emil Andreas (1889–1954)

- Isachsen, Gunnar (Gunnerius Ingvald) (1868-1939)

- Jacobsen, Theodor Claudius (1855-1933)

- Johansen, Fredrik Hjalmar (1867-1913)

- Juell, Adolf (1860-1909)

- Kakot

- Knudsen, Paul (1889-1919)

- Kristensen, Halvardus (1879 – 1919)

- Kristian Kristiansen (1865-1943)

- Kutschin, Alexander Stepanovich (1888 -1912)

- Lindstrøm, Adolf Henrik (1866-1939)

- Lund, Anton (1864–1945)

- Malmgren, Finn (1895-1928)

- Mogstad, Ivar Otto Irgens (1856-1928)

- Nilsen, Thorvald (1881-1940)

- Nordahl, Bernhard (1862-1922)

- Nødtvedt, Jacob (1857-1918)

- Olonkin, Gennadij (1898-1960)

- Olsen, Karenius (1890-1973)

- Olsen, Karl (1866-1939)

- Omdal, Oscar (1895-1927)

- Petterson, Lars (1860-1898)

- Prestrud, Kristian (1881-1927)

- Raanes, Oluf (1865-1932)

- Ramm, Fredrik (1892-1943)

- Ravna, Ole Nilsen (1841-1906)

- Riiser-Larsen, Hjalmar (1890–1965)

- Ristvedt, Peder (1873 – 1955)

- Rønne, Martin (1861-1932)

- Schei, Per (Peder Elisæus) (1875-1905)

- Schröer, Adolf Hermann (1872-1932)

- Scott Hansen, Sigurd (1868-1937)

- Simmons, Herman Georg (1866-1943)

- Stolz, Rudolf (1872- ??)

- Storm-Johnsen, Fridtjof (?-?)

- Stubberud, Jørgen (1883-1980)

- Sundbeck, Knut (1883 – 1967)

- Svendsen, Johan (1866-1899)

- Sverdrup, Harald Ulrik (1888-1957)

- Syvertsen, Søren Marentius (?? – 1923)

- Tessem, Peter Lorents (1875-1919)

- Tønnesen, Emanuel (1893–1972)

- Wiik, Gustav Juel (1878–1906)

- Wisting, Oscar (1871-1936)